PISA 2022 gets it right

by Keith Devlin @profkeithdevlin

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) provides international comparisons of national educational achievements

What image comes to mind when you hear a reference to the website for the Common Core State Standards for Mathematics? In particular, do you think of a single Web page, or a document that would require almost 100 pages to print out?

What are the most important parts of the document? If you were asked to provide a reporter with a sample of entries that effectively summarize what the document is about, what would you choose?

For me, this is a no brainer. By far, the most important part of the CCSSM are the eight Standards for Mathematical Practice. In fact, I would argue (and frequently have) that they are the only parts we should focus on (as goals to achieve).

To some extent, the folks who developed the Standards must have the same view. (For the record, I played no part in the development of the Standards.) The Mathematical Practices are listed right at the top. But for all the prominence given to their presentation, attention is rapidly swept away by the long and detailed matrix that follows. A matrix that focuses, in fine detail, on content. The eight Practices that capture the cognitive skill required to master and (then) utilize that content are hardly ever given any attention. Yet, if they are not mastered, all that content comes to naught.

Again, if you read the prose, the Standards developers clearly knew that. So too will anyone who knows what it is to develop and apply mathematics. But the Standards were written to meet the needs of the American education system. And for all the rhetoric, that system is not, in practice, focused on learning. It’s about assessment. The Mathematical Practices are about learning; the rest of the document is designed to meet the needs of assessment, in particular the kind of assessments that dominate US mathematics education, assessments that are required at regular intervals throughout a student’s school career. Assessments conducted for the most part by means of multiple-choice quizzes that are graded automatically.

Students, teachers, schools, and school districts are evaluated on the basis of those assessments. Mathematics learning, which should be focused on mastery of the Mathematical Practices, is reduced to training and practice aimed at meeting that myriad of content items that make up 97% of the CCSSM document. (I did the math. Well, I would, wouldn’t I? Three pages out of ninety total gives 3/90 x 100 = 3%, to the nearest whole number, on the MP.)

None of this is to say the CCSSM are bad. On the contrary; they do the best possible given the system in which they have to operate. In large part because the developers (clearly) knew what they were facing. In part too because significant efforts, by a great many experts, have been made to design multiple-choice content questions in a way that permits reasonably reliable inferences to be made as to students’ mathematical ability.

But surely, we can do better? And there is some hope we soon can. (Well, “soon” is a bit optimistic. But at least we now have a searchlight illuminating the terrain ahead.)

Just as national systemic assessments tend to drive teaching and pedagogy within a nation, assessments conducted to provide international comparisons across nations can push for changes in both pedagogy and testing within those nations. Political leaders are usually highly motivated by how well their country stacks up against other nations. This fact is fully understood by the good folks who run the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).

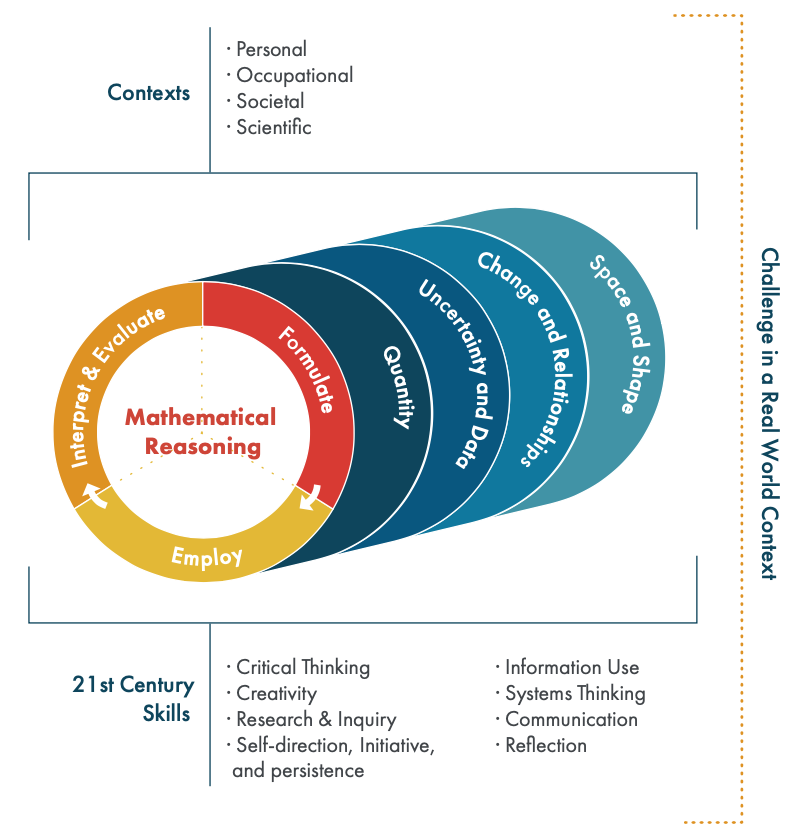

Interactive “index” for the different aspects of mathematics PISA 2022 says are the desired goals of math learning for the 21st Century. From https://pisa2022-maths.oecd.org/

I know this firsthand, from having interacted with some of them over the years. Unlike the CCSSM, I have taken part in a number of fact-finding, exploratory, and planning seminars and meetings aimed at formulating a new PISA framework for mathematics assessment. That new PISA 2022 Mathematics Framework has just been released.

It’s a very different document from the CCSSM. That’s a result of how it was developed. The starting point was the question, “What mathematical knowledge and skillsets does a person need for life in the 21st Century?”

The Web document just released is so well designed, I’m not going to discuss the content here. Just jump onto the site and explore it on your own.

I will say that it carves up mathematics in a very different way from the CCSSM. Instead of writing a matrix of standards to meet the requirements of systemic assessments of fine-grained content mastery, PISA focused on laying out a framework for mathematical learning for modern life, and in effect challenged the assessment business (which they are a part of) to come up with assessments that can measure how well students perform.

That is, to be sure, a significant challenge, as the PISA folks fully acknowledge. (See the PDF framework draft, downloadable from the website.) It’s a challenge that will likely take some years to meet. Systemic assessment is a complex enterprise, based on a highly inexact scientific base, made even more challenging by the impact it can have on people’s lives. Rapid change is not possible. Change at all will be slow to come.

But change there has to be. Right now, for the most part we assess only mathematical skills at tasks that can be—and generally are—performed by computer packages outside the math classroom. It makes no sense for that to be the bulk of what we assess today.

To my mind, the PISA 2022 Mathematics Framework, by telling us what is important for students to learn, and therefore what we need to measure, provides a goal for future assessments to aim for.

Top-level paragraph from the PISA 2022 document https://pisa2022-maths.oecd.org/

To be sure, the CCSSM set out to do that too, by leading off with the Mathematical Practices—which are what we should be measuring—but it provided an irresistible off-ramp by then listing a massive matrix of specific content knowledge that can readily be assessed. Even though that’s not (and in more recent times never was) what we really need to assess.

Ultimately, mathematics education is about helping people learn how to do/use mathematics in a variety of situations (what is frequently referred to as “mathematical thinking”). The Mathematical Practices try to capture that, albeit in a way that can come across as superficial, and hence not taken seriously, much like the messages you get on fortune cookies. The sheer mass of the detailed standards that follow end up getting most of the attention, so mathematics can appear to be all about acquiring a huge amount of detailed knowledge. And when that detailed knowledge is what we assess, the result is assessment of mathematical mastery by proxy. That can be, and has been, made to work tolerably well. The CCSSM were a big step forwards. But they don’t have to be the last step. PISA 2022 attempts to take the next step. And it’s a major one.

Since the CCSSM were offered as standards for learning—goals to guide teachers—they did not, strictly speaking, have to address systemic, summative assessments. Yet, the structure and content of current, systemic US assessment is what shaped the Standards.

In contrast, assessment is what PISA is all about, and that perspective has led them to craft a framework for learning, based on what really matters about mathematics learning.

It’s a shift from assessing what is most easily assessed and tailoring teaching to that end, to establishing what is important to teach and then developing assessments to measure that learning. That surely is the direction we should be going.

Anyway, enough of my musings. Take your own look at the Pisa 2022 website!