Monuments to Algebra

By Keith Devlin @KeithDevlin@fediscience.org

François Viète, b.1540 in Fontenay-le-Comte, France, d.1603, in Paris, France

2020 was the year when much of the world’s attention was focused on the progression of the novel coronavirus disease COVID-19. So it’s hardly surprising that the mathematical world missed the news that a commemorative plaque had been placed on the birthplace and childhood home of François Viète (1540–1603), one of the key figures in the development of modern algebra.

Placement of the plaque was announced on October 22, 2020 on the ouest-france website. Headlined Fontenay-le-Comte. A plaque affixed to the birthplace of François Viète, the story translates (my translation) as:

“For a long time, Fontenay-le-Comte and Foussais-Payré disputed the birthplace of the famous mathematician, François Viète. Today, things are clear. The Viètes did indeed own a property in Foussais-Payré, but the most illustrious of them, François, was born in the house located at 32, rue Gaston-Guillemet in Fontenay, in 1540. This has been authenticated by the local archivist Philippe Jaunet, who, during a search of the archives, discovered a deed of sale of the house by François Viète. A commemorative plaque has been affixed to the wall of the house, thanks to a donation from the Friends of the museum. The text was written by the academic Gaston Godard and the historian of mathematics Jean Dombres. It includes a summary of the biography of Viète. His studies at Fontenay-le-Comte and Poitiers, his law degree, his preceptorship to Catherine de Parthenay, his services to Kings Henry III and Henry IV. And of course his work on algebra with the introduction of letters into equations. In Fontenay-le-Comte, he was the friend of the illustrious, Rapin, Tiraqueau, Brisson, Rivaudeau... In 1651, he was honored by naming a crater on the moon after him.”

The story included a photograph of the new plaque, reproduced below. The text accompanying the photograph translates as (again, my translation):

“A commemorative plaque has been placed on the house where François Viète was born. It was placed artfully by the creator of the plaque, Philippe Guyonnet. Cost of the plate, 108 €.”

[The local archivist who finally found proof of Viète’s birthplace address, Phillipe Jaunet, a collaborator of the Vendée Archives for more than fifteen years, died aged 59 a year after the dedication, on September 27, 2021.]

Text of the commemorative plaque. On the left, the original French text, on the right my English translation. The “League” referred to in the text the Catholic League of France (Ligue catholique), sometimes referred to by contemporary Catholics as the Holy League (La Sainte Ligue). It was a major participant in the French Wars of Religion. The League was founded and led by Henri I, Duke of Guise, seeking the eradication of Protestantism from Catholic France, as well as the replacement of King Henri III (to whom Viète was an advisor). Pope Sixtus V, Philip II of Spain, and the Jesuits were all supporters of the League.

The small town of Fontenay-le-Comte lies south west of Paris, in the Poitou (now Vendée) Department of the Loire region. The Atlantic coast is just twenty miles away to the west; Nantes lays sixty miles to the north, Bordeaux is 150 miles to the south. The river Vendée flows through the town.

Fontenay had existed at least since the time of the Gauls. The “Comte” affix was (it is believed) added to its name when King Louis IX took it from the family of Lusignan and gave it to his brother Alphonse, count of Poitou, under whom it became capital of Bas-Poitou. The town was ceded to the Plantagenets by the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360, and subsequently retaken in 1372 by the Breton knight Bertrand du Guesclin (“The Eagle of Brittany”).

Today, Fontenay town presents itself as a tourist destination — “City of the Renaissance” — that has preserved the town (with improvements, of course) much as it was when Viète was born there. The Pays de Fontenay Vendée tourist website proudly declares (at time of writing, March 2023):

“The town of Fontenay-le-Comte holds the prestigious award “Town of Art and History,” counts among the “Most Beautiful Detours in France” and is the cradle of the philosophy of humanism. King François I nicknamed it the “fountain of beautiful minds.”

I haven’t visited it, but as a result of researching this story, I have it on my bucket list. It looks delightful.

Left: The plaque, affixed to the wall of the house built on the site of Viète’s birthplace and childhood home at 32, rue Gaston-Guillemet in Fontenay-le-Comte in October 2020. Right: A cropped image of the house at that address from Google Street View. The building seems old, but is built on the site of the one Viète was born in.

Most mathematicians, if asked to provide the five most significant figures in the chain of development that resulted in modern algebra would say Muḥammad al-Khwārizmī, (ca.780–ca.847), who lived at least most of his life in Baghdad, Leonardo “Fibonacci” (ca.1170–ca.1250), who was born and spent most of his life in Pisa, and three Frenchmen, Viète, Pierre de Fermat (1601–1665), and René Descartes (1596–1650).

Diophantus (200–284) is ruled out by the way the question is asked. He had a workable algebra long before any of those listed, but the development chain and the tradition that led to modern algebra began with the completion of al-Khwārizmī’s famous book Kitāb al-jabr wal-muqābala (Book on [Calculation by] Restoration and Confrontation). It introduced fundamental, and powerful methods to solve an equation: al-jabr (“restoration,” the transposition of subtracted terms to the other side of an equation) and al-muqābala (“confrontation,” the cancellation of like terms on opposite sides of the equation). The first of those two Arabic words led to our word “algebra”. Diophantus’s work influenced the development at various stages, but when you trace the tradition back in time from seventeenth century France, it stops with al-Khwārizmī. (If I had asked for the ten most significant figures in the chain, it would be much harder to decide the additional five to put in.)

The first two mathematicians in my list produced seminal texts, the final three turned what was until then a problem solving method of arithmetic (pre-modern algebra was essentially just “arithmetic with an unknown”), into a fully-fledged reasoning system with an internal logic.

As to the perennial question, “Who invented (pre-modern) algebra?” there is no definite answer. It was a tool with a long history, developed and improved upon in many parts of the world, by merchants, surveyors, civil engineers, and even jurists, to solve arithmetic problems that arose in their daily work. But the ancient origins of algebra is a story for another day.

The key advance Viète made was to treat coefficients and unknowns in equations as entities of the same type, so equations had an internal operational structure. Prior to that, symbols for the unknown were types (adjectives, if you will) that classified the numbers (nouns) that were their coefficients; so equations involved collections of different kinds of entity. (The term coefficient is due to Viète.)

For instance, in modern algebra, when we use a term such as 5x, we mean “5 multiplied by the unknown x”, and when we write 5x + 7 we mean “5 multiplied by the unknown x, added to 7”. But prior to Viète (in what is known as cossic algebra), 5x meant “5 objects of type x”, and 5x+7 meant “5 objects of type x lumped together with (not added to!) 7 units”. Quadratic terms were a totally different, third class of entity. And so on.

So pre-Viète, monomials and binomials were a bit like currency, where we use expressions such as “5 dollars” and “5 dollars and 7 cents”, or in the case of my childhood in the UK, “pounds, shillings, and pence” (which meant the currency I had to master had the structure of a quadratic trinomial expression). Yes, in those cases you can resolve everything into one kind of monetary token (e.g., cents or pence), but the calculus people use(d) to handle money keeps/kept them separate. The result is/was a cumbersome numerical calculus.

[For a brief description of premodern algebra in the style of al-Khwārizmī, click here.]

And (pre-modern) algebra was just a calculus. Viète took a major first step towards making algebra more versatile and streamlined, though that wasn’t his goal. Rather, as a geometer interested in astronomy, he wanted to develop a completely new algebra, not of numbers or numerical quantities, rather of geometric “magnitudes”, that would provide him with the machinery to more efficiently calculate astronomical tables. (He succeeded. His method was capable of constructing trigonometric tables in increments of 1’.)

Fermat and Descartes, who were born during Viète’s final years, both adopted his system in their own investigations, and in the process, Descartes in particular transformed it into the versatile, powerful framework of modern algebra that rapidly became the language of science and engineering.

Fermat monument

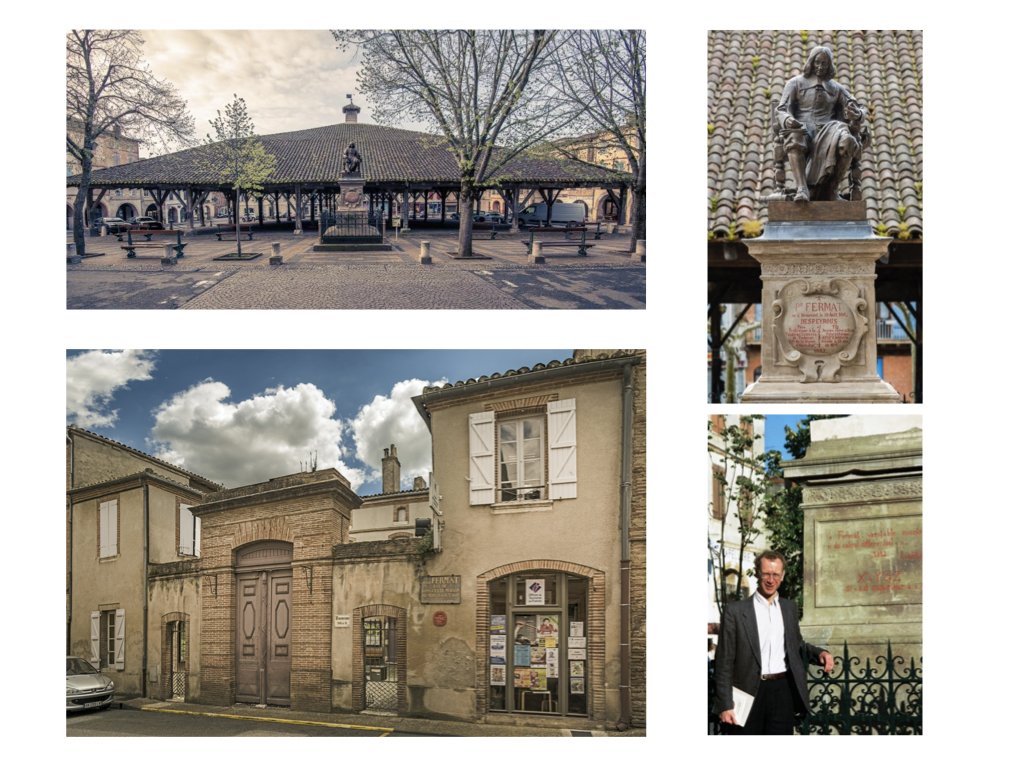

Both Fermat and Descartes have birthplace monuments honoring them. Fermat’s is in Beaumont-de-Lomagne, a commune in the Tarn-et-Garonne department in the Occitanie region in southern France, some 35 miles North East of Toulouse . The River Gimone runs through the town. Its population today is around 4,000. At the start of the seventeenth century it was little more than half that size. Beaumont’s main square, the Place Gambetta, is dominated by a large open-sided, wooden market hall built in the fourteenth century. The street that flanks the Gambetta on the north side is called Rue Pierre de Fermat. In front of the market hall, atop a tall plinth, is a life-sized statue of a scholarly-looking man, seated on a chair writing on a notepad on his knee. The inscription on the plinth gives the year the statue was erected: 1882.

A short walk from the hall leads to a brick-build house with the address 3 Rue Pierre de Fermat. For some years functioning as the Hotel Pierre de Fermat, the building today operates as the Beaumont-de-Lomagne tourist office, as well as housing an exhibition of mathematical games and puzzles. It is indexed in an official database of architectural heritage buildings maintained by the French Ministry of Culture, under the reference IA00038971 . Fermat was born in that house on August 17, 1601 and lived (parts of his life) there.

Beaumont-de-Lomagne. Clockwise starting top-left: (1) the fourteenth century wooden covered marketplace (still in use as such) in the Place Gambetta, with the statue of Fermat on a tall plinth, (2) close-up of the statue, (3) Andrew Wiles paying homage after finally proving Fermat’s Last Theorem, (4) the house where Fermat was born and lived part of his life.

Descartes’ monument

Where Fermat has a street named after him in the town of his birth, the village where Descartes was born not only has a Descartes Museum and a rue Descartes, they changed the village name itself to “Descartes”. Initially called La Haye-en-Touraine, today’s Descartes is a large commune in the Indre-et-Loire department in central France. It is just 35 miles south of Tours and under 20 miles to the east of Richelieu, situated on the banks of the Creuse River, near the border of the French department of Vienne, and the border of the region between Centre-Val de Loire and Nouvelle-Aquitaine. Paris lies almost 200 miles to the north.

The village of Descartes, France. Left the entrance to the Descartes Museum in the house where he was born and spent his childhood; right the statue of René Descartes in the center of the town.

The town was renamed La Haye-Descartes in 1802 in his honor, and then renamed again to Descartes in 1967. With a tiny population of little more than 1,500, in 1966 Descartes merged with the adjacent commune of Balesmes, giving a present-day population of around 3,600.

The house of Descartes’ birth is now the René Descartes House Museum, located at 29 rue Descartes, Descartes. The town also boasts a statue of their most famous child. (Curiously, one tourist website suggests (at the time of writing) that visitors who “are not students of the great man” should avoid the Descartes museum! Maybe they just want to ensure that mathematics and philosophy types have the place to themselves.)

Both of those towns (especially the museums!) are on my bucket list, along with Viète’s Fontenay.

Incidentally, there are statues of al-Khwārizmī and Leonardo, but they are relatively recent artist’s creations, and in neither case do we know what the individuals looked like. For al-Khwārizmī, we don’t know with any certainty where he was born.

Left. Statue of Leonardo of Pisa (“Fibonacci”) in the Camposanto in Pisa. Right. Statue of al-Khwārizmī in Khiva, a city in present-day Uzbekistan, in medieval times the capital of the Khwarazm region where al-Khwārizmī’s family (if not he himself) came from (hence the name). Both statues are artist’s creations.