Peak AP Calculus, What Comes Next? Part I

By: David Bressoud @dbressoud

David Bressoud is DeWitt Wallace Professor of Mathematics at Macalester College and Director of the Conference Board of the Mathematical Sciences

Over the many years that I have reported on the AP Calculus program, I have remarked on its phenomenal rate of growth that never seemed to slow down. It now has, leveling off at about 450,000 exams per year (Figure 1). That is an incredible number. In 2013, when 387,000 students took these exams, the U.S. Department of Education estimated that 19% of all high school graduates had taken a class in calculus. That fraction is certainly above 20% by now, probably between 750,000 and 800,000 students per year, with 55% to 60% of them taking the AP Calculus exam.

To get an idea of what these numbers mean, about 1.5 million students begin as full-time undergraduates in a 4-year program each fall. Just over half a million of them (516,000 in 2018) intend to major in a STEM field (Stolzenberg et al., 2019). About 360,000 complete a STEM degree each year (NCES, 2018). In Fall 2015, only 261,000 students enrolled in mainstream Calculus I at one of these colleges or universities. The 2015 MAA survey conducted by Progress through Calculus indicated that about 60% of students who enroll in Calculus I at any time do so in the fall term, suggesting that roughly 435,000 study Calculus I within a four-year undergraduate program each year, fewer than the number who take the AP exam.

Figure 1. Graph complied from data inherited from AP Chief Readers and College Board data available at https://research.collegeboard.org/programs/ap/data

The AP program is the driver behind calculus in high school. The College Board has estimated that 70% to 75% of the students who take AP Calculus will take the exam, so around 80% of high school calculus is AP Calculus, with the rest in dual enrollment, International Baccalaureate, or other courses simply labeled calculus. There is solid evidence that students who do well on the AP Exam and choose to use advanced placement to enroll directly in Calculus II are at least as well prepared as students who have studied Calculus I in college (summary of relevant reports can be found in Bressoud, 2009; a more recent study is in Patterson & Ewing, 2013). The problem is that only 199,000 students earned a 4 or higher on an AP Calculus exam in 2019, equivalent to a grade of A or B.

The conclusion from this cascade of data is that calculus, and specifically AP Calculus, has become part of the standard college preparatory curriculum. Students who possibly can take it, do. As stated in the opening paragraph, this is a bit over 20% of high school graduates. Students who want to stand out now need to do more than just show AP Calculus on their high school transcript.

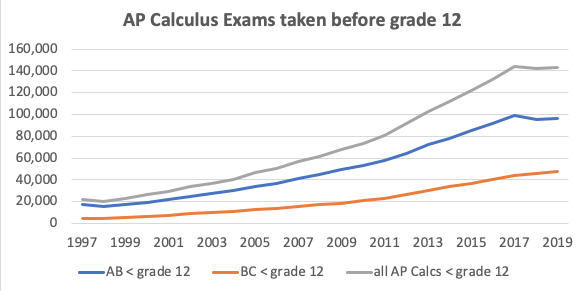

There are two ways in which this is happening, often connected. One is to take the AP course ever earlier. One drawback of the AP program is that the AP Calculus exams are administered after college admission decisions have been made. This means that there is little way for an admissions officer to distinguish between an AP course designed to look good on a transcript and one that truly prepares students for advanced placement. When the AP course is taken in the junior year or earlier, the results of the exam can be part of the student’s application. In 1997, 20,000 students took an AP Calculus exam before grade 12. By 2019 this number was over 143,000. For the BC exam, the numbers went from 4,000 in 1997 to 47,000 in 2019 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Graph compiled from College Board AP Data available at https://research.collegeboard.org/programs/ap/data

This hints at the other change created by the pressure to stand out: more students pursuing the BC course. When AP Calculus was established in 1955, there was just one calculus exam, covering the full year of college calculus. In 1969, a second calculus exam was created. The full year continued to be assessed as the BC exam, and the AB exam was introduced, based on slightly more than the standard first semester of college calculus including techniques of integration and applications of the definite integral.

Figure 3 shows the ratio of AB exams to BC exams. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, AB Calculus spread like wildfire, with the number of exams increasing more than fivefold from 1980 to 1995. BC Calculus lagged, partly because students have always had an option of which exam to take, and the AB exam often seemed a safer choice. The dramatic drop from 4.9:1 in 1997 to 4.3:1 in 1998 was the result of the introduction of an AB subscore on the BC exam. Much of the BC exam covers the same material as the AB exam, making it possible to provide students taking this exam with both an AB and a BC score. Students can take the BC exam, fail to score well enough for college credit for a full year, but still qualify for credit for half a year.

Figure 3. Graph complied from data inherited from AP Chief Readers and College Board data available at https://research.collegeboard.org/programs/ap/data

The College Board does not publish the comparison of BC scores and AB subscores, simply the total number of students earning each score on the BC portion and for the AB subscore. But the latest set of total numbers of students earning each score (College Board, 2019) is consistent with my expectation that about 2/3rds of the students score the same for BC and AB, about 1/3 score one point higher on AB than on BC, a very few students score two points higher on AB than BC, and almost no one does anything else.

Although I have no numbers to support this, there seems to be a growing movement of high school students who take Calculus AB one year and Calculus BC the next. If this is happening, it is troubling because Calculus BC was never intended to follow Calculus AB. There is simply not enough content beyond Calculus AB to justify a full-year course. And those students who choose to restart calculus when they get to college will have spent three years on the same material, a waste of their time and potential.

The rapid expansion of the College Board’s AP Calculus program has been of concern to the MAA at least since 1983 when the Committee on the Undergraduate Program in Mathematics issued the report of its Calculus Articulation Panel (CUPM, 1987). While the focus was on what high schools need to do to ensure the integrity of their calculus instruction, five of the Panel’s seventeen recommendations are directed at colleges and universities. The first two advise how to place these students (advanced placement should be restricted to those who score a 4 or 5). The remainder are worth repeating here because—37 years later—our colleges and universities have not done nearly enough along these lines, and the situation is now far more pressing.

15. Colleges should develop special courses in calculus for students who have been successful in accelerated programs, but have clearly not earned advanced placement.

Colleges have an opportunity and responsibility to develop and foster communication with high schools. In particular:

16. Colleges should establish periodic meetings where high school and college teachers can discuss expectations, requirements, and student performance.

17. Colleges should coordinate the development of enrichment programs (courses, workshops, institutes) for high school teachers in conjunction with school districts and State Mathematics Coordinators.

This is just Part I of this report because I have not yet touched on an enormous implication of the ubiquity of calculus in high school and the trend to push it ever earlier: the effect on issues of equity and access to mathematically intensive fields including science and engineering. I will explain what we know about this in next month’s column.

References

Bressoud, D. M. (2009). AP Calculus: What We Know. Launchings blogpost. Retrieved January 27, 2020 from https://www.maa.org/external_archive/columns/launchings/launchings_06_09.html

College Board. (2019). Student score distributions 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2020 from https://research.collegeboard.org/programs/ap/data/participation/ap-2019

Committee on the Undergraduate Program in Mathematics (CUPM). (1987). Report of the CUPM Panel on Calculus Articulation: Problems in the Transition from High School Calculus to College Calculus. The American Mathematical Monthly, 94(8), 776–785. Retrieved January 27, 2020 from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2323422.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2018). Bachelor's degrees conferred by postsecondary institutions, by field of study. Table 322.10. Retrieved January 27, 2020 from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_322.10.asp?current=yes

Patterson, B. F. and Ewing, M. (2013). Validating the Use of AP Exam Scores for College Course Placement. Research Report 2013-2. New York, NY: The College Board. Retrieved December 25, 2019 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED558108.pdf.

Stolzenberg, E. B., Eagan, M. K., Romo, E., Tamargo, E.J., Aragon, M.C., Luedke, M.,& Kang, N. (2019). The American Freshman: National Norms Fall 2018. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA. Retrieved January 27, 2020 from https://heri.ucla.edu/publications-tfs/

Download the list of all past Launchings columns, dating back to 2005, with links to each column.